MAKE YOUR OWN TRACKS!

Material abridged from: http://wildernessarena.com/overviews/animal-tracking-signs-guide

Any mark or disturbance we may see in nature tells a story.

Trackers call this “spoor” and it includes animal footprints (tracks!), animal droppings and other things like marks on trees or remains. Spoor tells a story and we human beings love stories. Spoor stories are vignettes – a brief and intimate peek into the life of another living being.

Identifying the species

You can use “animal cards” to help identify the species, buy a book on animal tracks and sign or of course, there are free and paid apps for that. For $4.99 we love MyNature for iphone and Android or the free app iTrackWlldlife Lite.

- Tracking is easiest in the morning and afternoon as shadows cast by ridges in the spoor are longer and stand out better

- After a rain is a good time to look for animal tracks around sand bars, washed sandy places, ditches, and gully washes.

- Trackers never look down at their feet but rather, look up and ahead approximately 15-30 feet in order to track faster.

- Trackers must avoid concentrating solely on the tracks and pay attention to everything around them.

- Expert trackers constantly vary their attention between the minute details of the track and the overall pattern of the environment they are moving through.

- Take care to not destroy the spoor. If the trail is lost, you can come back to an earlier point and restart from there.

To learn how to read spoor, experienced trackers consider 4 categories.

large-scale signs like trails. Look at the overall landscape and ecosystem. What animals habitat this area naturally? What would you expect to find?

- Transition areas – animals don’t live between ecosystems, like where the bog hugs the forest. Think of these transition area as animal roadways.

- Trails – animal trails, once established rarely change. They are used by different animal species. It is not uncommon for human trails, even roads, to have originated from an animal trail.

- Run – a run is a trail that might lead from a den to a watering hole, something used by a particular species. Runs can change when the animal moves on.

- Bed or sleeping area may include reeds that have been trodden down, a nest or den.

Subsurface trails – we see these a lot in the spring – think of worms moving soil so that we can trace their movements the next day. In the winter, mice will leave subsurface trails in the snow.

Feeding area- we may notice beavers who have felled saplings, bear that have trampled berry patches. We may also notice discarded pinecones at the base of tree indicating a squirrel.

Medium scale signs include rubs, gnaws, chews, scratchings, ground debris, upper vegetation breakage, above ground marks, bones, feathers, scat, kill sites, and more. Medium scale signs are often noticeable along runs and trails.

Small scale signs are difficult to discern and include compression and dust or grit left on the surface of an object. Animals walking either lift grit from the surface or compress it into the surface. This is called side-heading (because you’ll be tilting your head to get a closer look, using natural or artificial light to highlight details.

Ghost-scale signs – minute impressions on the ground including “dulling” where an animal may have wiped dew from the grass, or impressions left on leaves. A shining is a ghost-scale sign where nce vegetation dries out, animals passing over it press it down causing the shiny side of the grass to reflect sunlight. This effect, called a shining, disappears in about two hours. Note that bent grass recovers completely in about 24 hours.

The true track. The true track is the track that represents the true shape of the animal’s foot. A frequent tracking mistake is not considering the movement of the animal when the track is made. Measuring a track

Classifying tracks In most instances, there is not a track that can be seen clearly in soft soil with all toes visible. Thus, in 95% of the cases, you must use pattern classification in lieu of clear print classification to identify the animal.

Preferred gait First, determine the preferred gait of the animal to help differentiate between the front and rear tracks. The front and rear tracks will be in sets and near each other.

Number of toes Note the number of toes in the front track and the number of toes in the rear track. 2-toed tracks are often deer or elk. 3-toed tracks may be birds. 4-toed tracks could be rabbits, cats (mountain lions, bobcats), or dogs (foxes, coyotes). 5-toed tracks are weasels, skunks, and beavers.

Note that it is important to note the number of toes on both the rear and front tracks. Tracks with 5 rear toes and 4 front toes are mice, voles, shrews, chipmunks, squirrels, or porcupines.

Shape Note the overall shape of the track.

Register There are two types of registers. A direct register occurs when the rear track drops directly into the front track. As an animal lifts its front foot, the rear foot on the same side may drop directly into the front track. This is called “perfect walking” and is common in cats and foxes. An indirect register occurs when the rear foot drops slightly behind and left (or right) of the front track. As the animal picks up the front foot, the rear foot drops slightly behind and to the left (or right) of the front track (this behavior can help determine the sex of the animal).

Special considerations for birds Ground-based birds spend most of their time on land and will demonstrate a “walking” gait. Perching birds however, will typically exhibit a “hopping” gait. If a bird track shows both a walking and hopping gait, it is likely a species that spends time on both trees and on the ground (e.g. crows).

Pattern classification

Track “patterns” can be used when the tracks are not clear and easily recognizable (or may consist of only a compression in debris). To analyze using pattern classification, you must take into consideration the gait of the animal (its normal walking pattern).

The gait of an animal can be classified as diagonal walkers, bound walkers, gallop walkers, pacers, or some variation of these gaits.

Diagonal walkersDiagonal walkers, such as deer, dogs, and cats, move front and rear feet on opposite sides of the body at the same time. For instance, they step with the right front foot and left rear foot at

Bound walkers. Bounders from the weasel family, step with both front feet followed by both rear feet behind the front feet. They hop and leap by placing their front feet down and in one motion, they lift their front feet up and place their hind feet down in the same spot. Bound walkers nearly always walk using this pattern regardless of their pace (it is a very energy efficient means of locomotion).

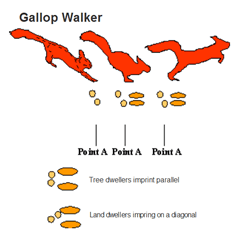

Gallop walkersThe front feet land first followed by the rear feet landing on the outside of the front feet and slightly ahead. With these animals, the pattern doesn’t change with speed but rather, the distance between the sets of tracks and is common with rabbits and rodents.

Pacers front and rear feet on the same side of the body at the same time, they step with the right front foot and right rear foot at the same time. Common with animals that have large, rounded bodies such as badgers, skunks, porcupine, opossum, raccoon, and bears. Pacers sometimes change their pattern as their speed increases.

Variations About 5% of the time an animal will change their gait or pattern.

The age of a track Weather, weather fluctuations, gravity, and type of soil all contribute to a track’s aging process.

Maybe you’ve always considered animal tracks a trivial thing. Think about this the next time you walk down a city street:

The Calf-Path

Sam Foss

I.

One day through the primeval wood

A calf walked home as good calves should;

But made a trail all bent askew,

A crooked trail as all calves do.

Since then three hundred years have fled,

And I infer the calf is dead.

II.

But still he left behind his trail,

And thereby hangs my moral tale.

The trail was taken up next day,

By a lone dog that passed that way;

And then a wise bell-wether sheep

Pursued the trail o’er vale and steep,

And drew the flock behind him, too,

As good bell-wethers always do.

And from that day, o’er hill and glade.

Through those old woods a path was made.

III.

And many men wound in and out,

And dodged, and turned, and bent about,

And uttered words of righteous wrath,

Because ‘twas such a crooked path;

But still they followed—do not laugh—

The first migrations of that calf,

And through this winding wood-way stalked

Because he wobbled when he walked.

IV.

This forest path became a lane,

that bent and turned and turned again;

This crooked lane became a road,

Where many a poor horse with his load

Toiled on beneath the burning sun,

And traveled some three miles in one.

And thus a century and a half

They trod the footsteps of that calf.

V.

The years passed on in swiftness fleet,

The road became a village street;

And this, before men were aware,

A city’s crowded thoroughfare.

And soon the central street was this

Of a renowned metropolis;

And men two centuries and a half,

Trod in the footsteps of that calf.

VI.

Each day a hundred thousand rout

Followed the zigzag calf about

And o’er his crooked journey went

The traffic of a continent.

A Hundred thousand men were led,

By one calf near three centuries dead.

They followed still his crooked way,

And lost one hundred years a day;

For thus such reverence is lent,

To well established precedent.

VII.

A moral lesson this might teach

Were I ordained and called to preach;

For men are prone to go it blind

Along the calf-paths of the mind,

And work away from sun to sun,

To do what other men have done.

They follow in the beaten track,

And out and in, and forth and back,

And still their devious course pursue,

To keep the path that others do.

They keep the path a sacred groove,

Along which all their lives they move.

But how the wise old wood gods laugh,

Who saw the first primeval calf.

Ah, many things this tale might teach—

But I am not ordained to preach.